Color Blindness: Understanding Red-Green Defects and How They're Inherited

Most people think color blindness means seeing the world in black and white. But that’s not true for the vast majority of people with the condition. In fact, red-green color blindness isn’t blindness at all-it’s a mismatch in how your eyes process certain colors. If you’re one of the 8% of men or 0.5% of women affected, you’re not missing color entirely. You’re just struggling to tell reds, greens, browns, and oranges apart. And the reason why this happens is deeply tied to your genes.

Why Men Are More Likely to Be Color Blind

The biggest clue that this is a genetic issue? The numbers don’t add up evenly between men and women. About 1 in 12 men has some form of red-green color blindness. For women, it’s closer to 1 in 200. That’s not a coincidence. It’s biology.

The genes that control your red and green color vision sit on the X chromosome. Men have one X and one Y chromosome. Women have two X chromosomes. If a man inherits a faulty color vision gene on his single X chromosome, he has no backup. He’ll be color blind. A woman needs two faulty copies-one on each X chromosome-to show the same level of deficiency. That’s rare. Even if she carries one bad copy, her other X chromosome often compensates.

This is why red-green color blindness follows an X-linked recessive pattern. It’s not just a quirk-it’s a predictable genetic outcome. A mother who carries the gene can pass it to her sons. A father with color blindness can’t pass it to his sons (because he gives them his Y chromosome), but he will pass it to all his daughters, making them carriers.

What’s Actually Happening in Your Eyes

Your retina has three types of cone cells, each sensitive to different wavelengths of light: short (blue), medium (green), and long (red). The green and red cones are the ones that usually cause trouble. Their light-sensitive proteins-called photopsins-are made by two genes: OPN1MW for green and OPN1LW for red. Both are located side-by-side on the X chromosome.

Here’s where things get messy. These genes are so close together that they sometimes swap pieces during reproduction. This is called unequal recombination. The result? A person might end up with no red gene, two green genes, or a hybrid gene that acts like a mix of both. That’s what leads to different types of red-green color blindness.

There are four main types:

- Protanopia: No functional red cones. Reds look dark or brownish, and some greens appear yellow.

- Deuteranopia: No functional green cones. Reds and greens look very similar, often muddy or beige.

- Protanomaly: Red cones are present but faulty. Reds look duller and less bright.

- Deuteranomaly: Green cones are faulty. This is the most common form-about 5% of men have it. Colors aren’t gone, just confused.

Deuteranomaly is so common because the green gene array is more prone to recombination errors. It’s not a defect-it’s a quirk of how our DNA is structured.

How It’s Diagnosed-and Why It Matters

The Ishihara test is still the gold standard. Those plates with colored dots that form numbers? They’ve been around since 1917. But they’re not perfect. Some people with mild deuteranomaly pass them, while others with normal vision might fail due to poor lighting or fatigue.

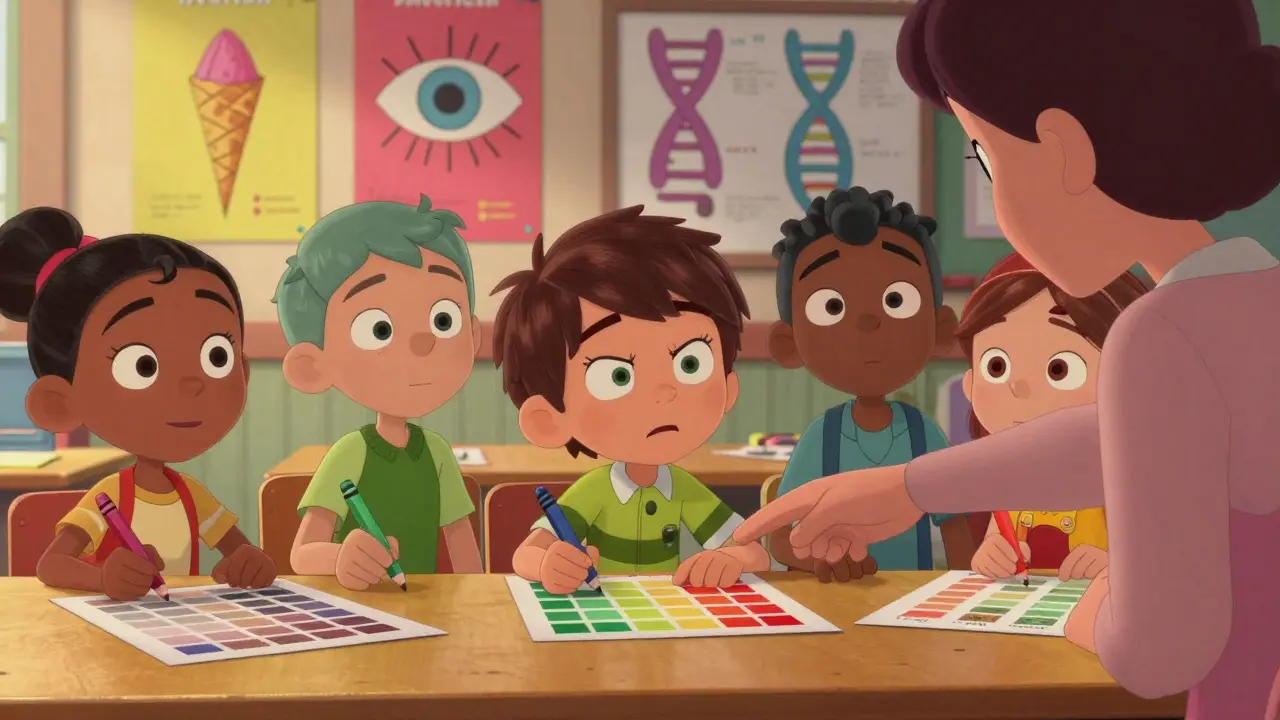

More accurate tests now exist, like the Farnsworth-Munsell 100 Hue Test or the anomaloscope, which lets you mix red and green light to match a yellow. But most people never get tested unless they’re applying for a job that requires color vision-like aviation, electrical work, or graphic design.

And that’s where the real impact shows up. A pilot applicant with protanopia might be turned away, even though their vision is 20/20. An electrician might mix up red and green wires. A student might miss color-coded graphs in class. A designer might pick a palette that’s unreadable to a quarter of their audience.

Life With Color Blindness: Real Stories

One Reddit user, who identifies as a protanope, shared how he failed his commercial pilot medical exam-not because he couldn’t see clearly, but because he couldn’t tell the difference between red and green runway lights. He’s a skilled pilot, but the rules don’t bend for color vision.

Another user, a graphic designer with deuteranomaly, says she used to rely on colleagues to check her palettes. Then she started using tools like Color Oracle and Sim Daltonism. Now she designs with contrast and patterns first, color second. She says it made her work better.

And it’s not just about work. A 2022 survey by Colour Blind Awareness found that 78% of people with red-green color blindness struggled with color-coded educational materials. Over 60% had trouble with traffic lights in foggy weather. Nearly half said apps and websites were hard to use because text blended into backgrounds.

But here’s the surprising part: 92% of those surveyed didn’t see it as a disability. Just an inconvenience. Most learn to adapt. They label wires. They use apps to identify colors. They ask for help. They don’t see themselves as broken-they just see the world differently.

Can It Be Fixed?

No cure exists yet. But there are tools that help.

EnChroma glasses, introduced in 2012, use special filters to block overlapping wavelengths of light. They don’t give you normal color vision. But for about 80% of people with deuteranomaly or protanomaly, they make reds and greens feel more distinct. The catch? They cost $300-$500. And they don’t work for everyone-especially not for those with complete absence of one cone type.

There’s also software. Apple and Windows both have built-in color filters. Microsoft’s tool has been used over 2.3 million times. Apple’s is enabled by 0.8% of iPhone users. That might sound small, but it’s millions of people adjusting their screens to see better.

And then there’s the ColorADD system-a universal symbol-based color code developed in Portugal. It’s now used in public transit systems across 17 countries. A red bus isn’t just red-it has a triangle symbol. Green is a circle. It’s simple, effective, and doesn’t rely on sight.

The Future: Gene Therapy and Accessibility

Science is moving fast. In 2022, researchers at the University of Washington used gene therapy to restore full color vision in adult squirrel monkeys with red-green color blindness. The effect lasted over two years. That’s not a human trial yet-but it’s proof that the brain can learn to use new color signals, even in adulthood.

The National Eye Institute is investing millions into restoring color vision as part of its long-term goals. While a cure isn’t coming next year, it’s no longer science fiction.

In the meantime, accessibility is improving. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) now require websites to use more than color to convey information. That means icons, labels, patterns, and contrast ratios. EU law requires public websites to follow these rules. Even big tech companies are building color-blind-friendly interfaces.

And the market is responding. The global color blindness testing and assistive tech market is expected to grow from $148 million in 2022 to over $215 million by 2027. More people are being diagnosed. More tools are being made. More workplaces are adapting.

What You Can Do

If you think you might have red-green color blindness, get tested. It’s not about labels-it’s about understanding how you see the world. Many people live their whole lives without knowing.

If you’re a designer, developer, or educator: stop relying on color alone. Add patterns, labels, and contrast. Use tools like Color Oracle to simulate what your audience sees.

If you know someone who’s color blind: don’t assume they’re making mistakes. Ask how you can help. Maybe it’s labeling your crayons. Maybe it’s using a different chart. Small changes make a big difference.

Red-green color blindness isn’t a tragedy. It’s a variation. And like any variation, it comes with challenges-but also with resilience, adaptation, and innovation.

Can color blindness get worse over time?

No. Red-green color blindness is congenital, meaning it’s present from birth and doesn’t change. It’s not degenerative like macular degeneration. Your color vision will stay the same throughout your life. However, other eye conditions-like cataracts or aging-can make color perception harder for anyone, even those without inherited color vision deficiency.

Can women be color blind?

Yes, but it’s rare. A woman needs to inherit the faulty gene from both her mother and father to have full red-green color blindness. Since the gene is on the X chromosome, and men only have one, it’s much more likely for a man to be affected. About 0.5% of women have the condition, compared to 8% of men. Some women with one faulty gene may have slightly altered color perception, but they rarely experience the full effect.

Are color blind glasses worth it?

It depends. For people with deuteranomaly or protanomaly, many report a noticeable improvement in distinguishing reds and greens-especially in natural light. But they don’t restore normal color vision, and they don’t work for those with complete absence of red or green cones. They’re expensive ($300+), and results vary. Try them with a trial period if possible. For many, digital tools or simple adaptations are more practical and cost-effective.

Can you outgrow color blindness?

No. Color blindness is genetic and permanent. Children are born with it, and it doesn’t go away. Some kids learn to compensate early-using brightness or context to guess colors-but the underlying condition stays the same. Early testing can help families and schools make accommodations before it becomes a problem in learning or daily life.

Does color blindness affect daily life significantly?

For most people, not in a major way. The biggest issues are in specific situations: reading color-coded charts, matching clothes, identifying ripe fruit, or distinguishing wires in electronics. Many people adapt without even realizing they’re doing it. But in high-stakes fields like aviation, medicine, or electrical work, it can be a barrier. Awareness and accessibility tools have made life much easier than it was 20 years ago.

Red-green color blindness isn’t a flaw. It’s a variation in human biology, shaped by evolution, genetics, and chance. Understanding it isn’t just about science-it’s about seeing the world more clearly, for everyone.

Liz Tanner

December 27, 2025 AT 00:43I’ve lived with deuteranomaly my whole life and never knew why I kept mixing up my socks. Learning it was genetic was a relief. I used to think I was just bad at fashion. Turns out, my brain just sees the world differently. No shame in that.

Now I label everything. My pens, my wires, even my spice jars. It’s not a fix, but it’s a hack that works. And honestly? I don’t miss what I never knew I was missing.

Also, Color Oracle saved my design career. If you’re a creator, try it. It’s free. You’ll thank me later.

Babe Addict

December 28, 2025 AT 08:09Let’s be real-this whole ‘color blindness’ narrative is a medicalized misnomer. You’re not ‘blind,’ you’re spectrally anomalous. The cones are there, just misexpressed due to unequal recombination of OPN1LW and OPN1MW on Xq28. The X-linked recessive inheritance pattern is textbook, but the real issue is societal design failure, not biological deficiency.

EnChroma glasses? They’re just optical filters that attenuate overlapping wavelengths. They don’t restore trichromacy-they create a perceptual illusion. And don’t get me started on ColorADD. Symbolic encoding is a band-aid for lazy UI design. We should be redesigning systems, not medicating perception.

Satyakki Bhattacharjee

December 28, 2025 AT 08:30God made men and women different for a reason. Men get color blindness because they are weaker in spirit. Women have two X chromosomes, so they are stronger. This is not science-it is divine order.

Why do you think so many men fail in life? Because they see the world wrong. They cannot tell red from green, just like they cannot tell right from wrong.

Fix the system, not the man. God’s design is perfect. We are the ones who broke it with technology.

Kishor Raibole

December 29, 2025 AT 23:58One cannot help but observe, with profound intellectual consternation, the contemporary tendency to pathologize neurodivergence under the euphemistic banner of 'color vision deficiency.'

One is led to inquire: Is the failure of societal infrastructure-be it traffic signals, educational materials, or digital interfaces-a reflection of collective negligence, or merely the inevitable consequence of biological variance?

And yet, we persist in prescribing corrective lenses, rather than reimagining the architecture of perception itself. The irony is not lost upon the discerning observer.

John Barron

December 30, 2025 AT 06:58Okay, but let’s talk about the real tragedy here: 80% of people with deuteranomaly report improved color distinction with EnChroma glasses… and yet, insurance doesn’t cover them. 😔

Meanwhile, my cousin’s kid got a $10,000 gene therapy trial for spinal muscular atrophy, and I’m supposed to be okay with paying $500 for a pair of sunglasses that help me tell my red shirt from my green one? 🤡

Also, I have a 20/10 vision and I can see the difference between red and green… so why is this even a thing? 🤔

Liz MENDOZA

December 30, 2025 AT 07:26Reading this made me think of my brother. He’s a pilot, and he passed his medicals because he memorized the order of the lights-red on top, green on bottom. He never told anyone he couldn’t tell them apart until he was 30.

He’s not broken. He’s brilliant. He adapted. And now he trains new pilots to look for patterns, not just colors.

If you’re designing something, ask someone who’s color blind. Not for pity. For insight. They see things you don’t.

Anna Weitz

December 31, 2025 AT 19:06Why do we even call it color blindness when it’s not blindness at all? It’s just a different color map. Like how some people see music as shapes. It’s not a defect, it’s a different operating system

And honestly? I think people with it see more nuance. They notice contrast, texture, shape. They don’t rely on the lazy shortcut of color

Stop treating it like a disease and start treating it like a feature

Jane Lucas

January 1, 2026 AT 06:55i had no idea my dad was color blind until he tried to pick out my prom dress and said ‘that one looks nice’ and it was neon green and purple

he just thought it was brown

we still laugh about it

Caitlin Foster

January 1, 2026 AT 16:07Wait-so EnChroma glasses cost $500?!?!?! And they don’t even work for everyone?!?!?! And we’re supposed to just… accept that?!?!?!

Meanwhile, my phone has a color filter that I turned on because I thought it was a glitch… and now I can see the difference between red and green traffic lights?!?!?!

Why isn’t this built into EVERYTHING?!?!?! Why are we still using color-coded charts?!?!?!

Someone needs to start a revolution. Like, NOW. 🤯💥

Raushan Richardson

January 2, 2026 AT 13:41I’m a graphic designer and I have deuteranomaly. I used to stress over every palette. Then I started using contrast checkers and pattern overlays. Now my designs are clearer for everyone-even people with perfect vision.

Turns out, making things accessible isn’t just nice-it’s better design.

Also, I have a little sticker on my laptop that says ‘I see colors differently.’ It starts conversations. And honestly? That’s kind of cool.