FDA’s Abbreviated New Drug Application Process Explained: How Generic Drugs Get Approved

Every time you pick up a prescription and see a lower price tag than the brand-name version, you’re seeing the ANDA process at work. The Abbreviated New Drug Application isn’t just a bureaucratic form-it’s the engine behind 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. It’s how generic drugs, often costing 85% less than their brand-name counterparts, reach pharmacy shelves without repeating every clinical trial ever done. But how does it actually work? And why do some generic applications get approved in months while others stall for years?

What Is the ANDA Process, Really?

The ANDA process, created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, lets generic drugmakers skip the expensive, time-consuming path of proving a drug is safe and effective from scratch. Instead, they only need to prove their version is the same as an already approved brand-name drug-the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). That’s the whole point of “abbreviated.” No need to retest safety in thousands of patients. No need to repeat years of animal studies. The FDA already did that. The generic maker just has to show they can make an identical copy.It sounds simple, but it’s not. The FDA doesn’t just accept “close enough.” The generic must match the RLD in every meaningful way: same active ingredient, same strength, same pill shape or liquid form, same way it’s taken (oral, injected, inhaled), and same labeling. Even the color of the pill matters if it affects how patients recognize it. The manufacturing process must follow current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), and the facility must pass a strict inspection. If any part fails, the application gets rejected.

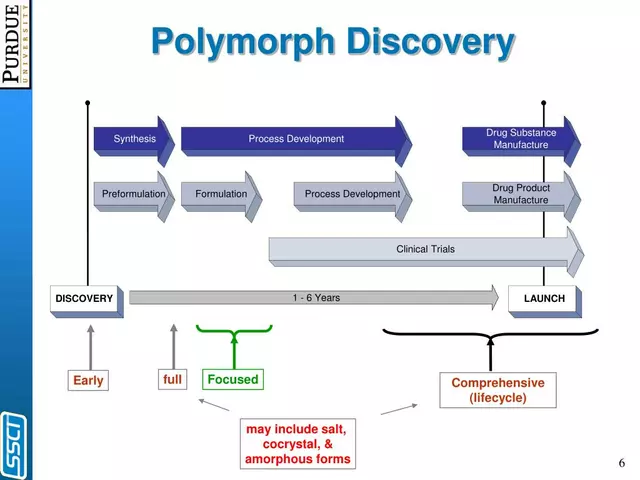

How the ANDA Review Timeline Actually Works

The FDA doesn’t just sit on applications. There’s a clear, structured review process with four phases:- Filing Review: Within 60 days of submission, the FDA checks if the application is complete. Missing forms? Incomplete data? It gets sent back. About 15% of applications get rejected here.

- Discipline Reviews: Teams of scientists review different parts: chemistry, manufacturing, bioequivalence, labeling. Each team looks for flaws. A bioequivalence study showing 95% absorption instead of 100%? That’s a red flag. A labeling section missing a warning about kidney patients? That’s a problem.

- Information Requests and Responses: This is where most delays happen. The FDA sends out Information Requests (IRs)-detailed questions asking for more data, clarification, or corrections. One company reported getting 17 IRs across seven different teams. Responding to each takes weeks or months. If the FDA thinks the application can’t be fixed, they issue a Complete Response Letter (CRL).

- Final Approval or Tentative Approval: If everything checks out and there are no patent or exclusivity blocks, the FDA gives Final Approval. If there’s a patent still in effect, they give Tentative Approval. That means the drug is scientifically approved but can’t be sold until the patent expires.

Under GDUFA III (effective 2022), the FDA aims to review original ANDAs in 10 months. But the average time from submission to approval is still around 30 months. Why? Because many applications get bogged down in IRs, inspections, or patent disputes. Complex generics-like inhalers, topical creams, or injectables-take even longer because proving equivalence is harder.

ANDA vs NDA: Why Generic Drugs Cost So Much Less

The difference between a generic application (ANDA) and a brand-name application (NDA) is like comparing a used car inspection to building a new car from the ground up.An NDA under Section 505(b)(1) requires full clinical trials-hundreds of patients, years of data, millions of dollars. The Tufts Center estimates it costs $2.3 billion to bring a new drug to market. That’s why brand-name drugs start at hundreds or even thousands of dollars per pill.

An ANDA under Section 505(j) only needs bioequivalence data. That’s usually one small study with 24-36 healthy volunteers. The generic drug is given, blood samples are taken, and scientists check if the body absorbs it at the same rate and amount as the brand. The cost? Between $1 million and $5 million. That’s why a 30-day supply of generic lisinopril costs $4 instead of $120.

There’s also a middle path-the 505(b)(2) NDA-used for slightly modified drugs, like a new dosage form or a combo pill. It allows some reliance on the brand’s data but still requires new clinical work. It’s not a shortcut like the ANDA.

Why Do So Many ANDAs Get Rejected?

The approval rate for first-cycle ANDAs is 91%, which sounds high. But that means nearly 1 in 10 applications fail outright. And of those that get reviewed, 78% get at least one Information Request. The biggest reasons for rejection:- 35%: Inadequate bioequivalence studies. Too few participants, wrong timing of blood draws, poor statistical analysis. A study showing 88% absorption instead of 100%? That’s not equivalent.

- 28%: Manufacturing or facility issues. The FDA inspects factories before approval. If the facility has cleanliness problems, data integrity issues, or unapproved equipment, the application stalls.

- 22%: Labeling errors. Missing warnings, wrong dosage instructions, or inconsistent language compared to the brand. Even a typo can trigger a rejection.

One manufacturer spent $1.2 million and three tries to get bioequivalence right for a topical cream. The active ingredient behaved differently when mixed with certain emulsifiers. That’s the hidden cost of generics: the science is simpler, but the precision is extreme.

Who’s Winning the Generic Game?

The generic drug market is dominated by a few big players. Teva Pharmaceuticals holds about 22% of the U.S. market. Viatris (formerly Mylan) has 15%, and Sandoz has 12%. But 75% of ANDAs come from companies that already have five or more approved generics. Experience matters.Companies that succeed have systems: dedicated regulatory teams, pre-submission meetings with the FDA, and internal checklists based on FDA’s 2,000+ product-specific guidances. One VP at Teva said after their tenth ANDA, they hit approval within GDUFA timelines 92% of the time. That’s not luck-it’s process.

Smaller companies struggle with the complexity. A single ANDA can require 5,000-10,000 hours of work across chemistry, manufacturing, clinical, and regulatory teams. That’s why many small firms partner with contract research organizations or outsource bioequivalence studies.

What’s Changing in the ANDA Process?

The FDA is adapting. In 2018, they launched the Complex Generic Drug Products Initiative because creams, inhalers, and injectables are harder to copy than pills. These products need new testing methods. Today, 35% of pending ANDAs are for complex generics.The FDA now uses AI-assisted tools in 78% of chemistry reviews to spot inconsistencies faster. They’re also exploring real-world data-like pharmacy claims and patient outcomes-to support approvals for certain generics.

But challenges remain. Patent thickets-where brand companies file dozens of minor patents to block generics-still delay access. REMS programs (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies) sometimes restrict generic access by limiting distribution. And with 14,000 generic products on the market, competition is fierce. The price of a generic drug can drop to 15% of the brand’s price within a year of entry.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, the ANDA process means lower bills. It means you can afford your blood pressure med, your insulin, your antidepressant. It’s why the U.S. healthcare system saved $373 billion in 2021 from generic drugs alone.If you’re a pharmacist, you know which generics are reliable-and which ones have had delays or recalls. You’ve seen patients switch from brand to generic and wonder if it’s the same. It is. The FDA ensures it.

If you’re in the industry, the ANDA process is a high-stakes game of precision. One misplaced decimal in a bioequivalence report can cost you a year. But for those who get it right, it’s a reliable path to market.

The ANDA process isn’t perfect. It’s slow. It’s complex. It’s expensive to get right. But it works. It’s the reason millions of Americans can afford their prescriptions. And as long as the FDA keeps refining it-using science, not bureaucracy-it will keep saving lives and money.

Is a generic drug exactly the same as the brand-name version?

Yes, in every way that matters for safety and effectiveness. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, route of administration, and labeling as the brand-name drug. The only differences are in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes), which don’t affect how the drug works. Some people notice slight differences in pill shape or color, but the medicine inside is identical.

Why does my generic drug look different from the brand?

U.S. law requires generic drugs to look different from the brand-name version to avoid trademark infringement. That means the pill may be a different color, shape, or size. But the active ingredient-and how your body absorbs it-must be the same. If you’re concerned about effectiveness, talk to your pharmacist. The FDA ensures bioequivalence before approval.

Can a generic drug be less effective than the brand?

No, not if it’s FDA-approved. The FDA requires generics to deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. Studies show no meaningful difference in effectiveness between approved generics and brand-name drugs. If you feel a difference, it could be due to inactive ingredients affecting how you tolerate the pill-not how well it works.

What’s the difference between Tentative Approval and Final Approval?

Tentative Approval means the FDA has found the generic drug scientifically equivalent and safe, but it can’t be sold yet because a patent or exclusivity period is still active on the brand-name drug. Final Approval means all legal barriers are cleared, and the generic can be marketed immediately. Many companies wait for Tentative Approval to prepare for launch the day the patent expires.

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved?

On average, it takes about 30 months from submission to approval. But the FDA’s goal under GDUFA III is to approve original ANDAs within 10 months. Complex generics, like inhalers or injectables, can take much longer-sometimes over 5 years-because proving equivalence is harder. Delays often come from information requests, facility inspections, or patent disputes.

Angel Tiestos lopez

January 14, 2026 AT 09:24Alan Lin

January 15, 2026 AT 12:49Nelly Oruko

January 16, 2026 AT 00:52vishnu priyanka

January 16, 2026 AT 04:28Adam Vella

January 17, 2026 AT 19:20Trevor Whipple

January 17, 2026 AT 20:15Lethabo Phalafala

January 19, 2026 AT 19:20Lance Nickie

January 20, 2026 AT 19:57Milla Masliy

January 20, 2026 AT 23:03Damario Brown

January 21, 2026 AT 12:18sam abas

January 23, 2026 AT 08:32John Pope

January 24, 2026 AT 22:41Clay .Haeber

January 25, 2026 AT 01:00