Acromegaly and Pituitary Tumors: What’s the Connection?

Acromegaly Symptom Checker

Symptom Assessment Tool

This tool helps you identify potential acromegaly symptoms. The article explains that acromegaly symptoms develop slowly and may be mistaken for normal aging. If you're experiencing multiple symptoms, consult a healthcare professional for proper evaluation.

Your Results

Select symptoms to see your assessment.

Understanding acromegaly is the first step toward figuring out why a seemingly harmless pituitary tumor can change a person’s life. While the two conditions sound technical, the link between them is surprisingly straightforward: a tumor in the pituitary gland can hijack hormone production, leading to excessive growth hormone and the cascade of symptoms we call acromegaly.

What Is Acromegaly?

Acromegaly is a rare hormonal disorder that occurs when the body is exposed to too much growth hormone (GH) after the growth plates have closed. Because the skeleton can no longer lengthen, excess GH causes the soft tissues and bone to thicken instead. Most patients notice changes in their hands, feet, and facial features rather than a dramatic increase in height.

The condition develops slowly, often over many years, so many people attribute the changes to normal aging. Early diagnosis matters because untreated acromegaly raises the risk of cardiovascular disease, type‑2 diabetes, sleep apnea, and joint problems.

What Are Pituitary Tumors?

Pituitary tumor refers to any abnormal growth within the pituitary gland, a pea‑sized organ at the base of the brain that regulates dozens of hormones. Most pituitary tumors are benign adenomas, meaning they are non‑cancerous but can still disrupt hormone balance.

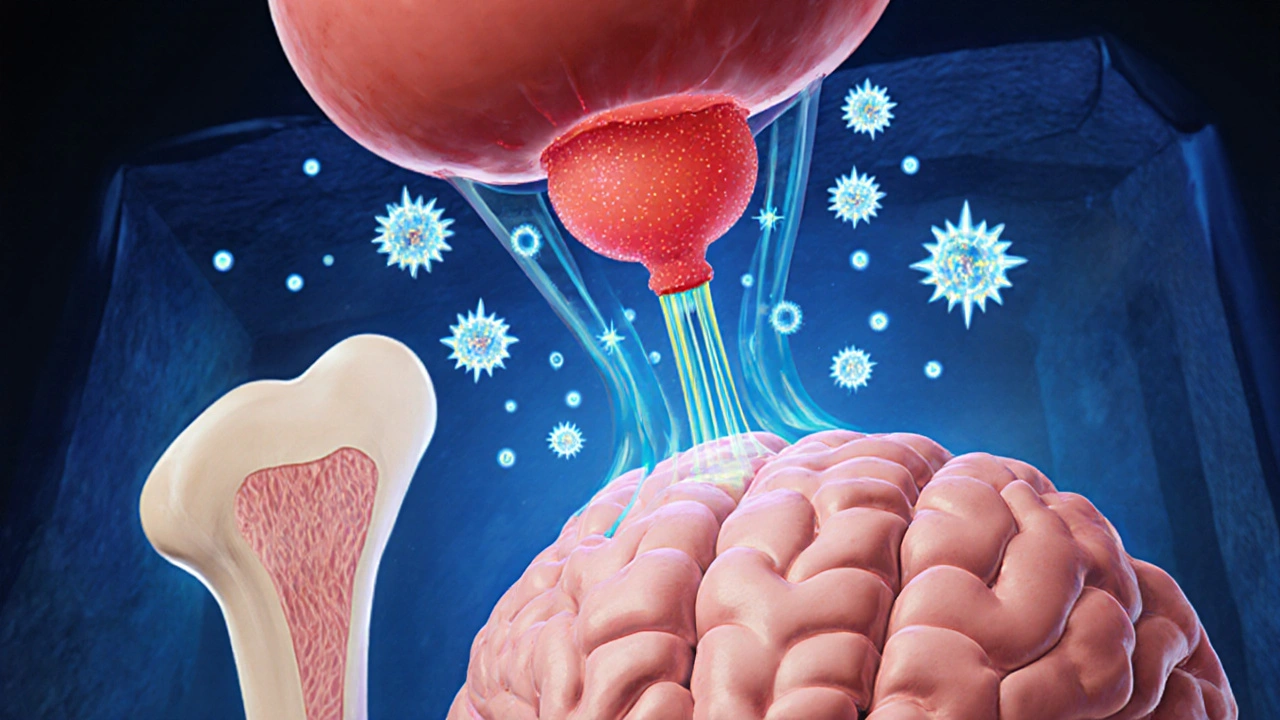

When the tumor originates from somatotroph cells-those that produce growth hormone-it’s called a somatotroph adenoma. This specific type is the primary driver of acromegaly. Other adenomas may secrete prolactin, ACTH, or remain non‑functioning, causing symptoms only through mass effect.

How the Tumor Triggers Hormone Overproduction

The pituitary’s job is to release hormones in response to signals from the hypothalamus. A growing adenoma can either: (1) directly overproduce GH, or (2) compress normal pituitary tissue, interfering with feedback loops that usually keep GH levels in check. The result is chronic elevation of GH and, consequently, higher levels of insulin‑like growth factor‑1 (IGF‑1) in the bloodstream.

IGF‑1 is the molecule that actually drives the tissue‑growth effects seen in acromegaly. Measuring IGF‑1 gives doctors a reliable snapshot of average GH activity over the previous few days, which is why it’s a cornerstone of diagnosis.

Signs and Symptoms to Watch For

- Enlarged hands and feet-ring sizes increase, shoe sizes jump.

- Coarsening of facial features-pronounced jaw (prognathism), enlarged nose, thickened lips.

- Skin changes-oilier, thickened skin that may develop acne or skin tags.

- Joint pain and arthritis due to excess cartilage growth.

- Headaches or visual field defects (bitemporal hemianopsia) from tumor pressure on the optic chiasm.

- Metabolic issues-insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and lipid abnormalities.

Because many of these signs appear gradually, patients often seek medical help only after the changes become obvious to family members.

Diagnostic Pathway

The work‑up for a suspected pituitary source follows a clear sequence:

- Clinical suspicion: Primary care or endocrinology visit based on the physical changes listed above.

- Biochemical testing: Random GH levels are variable, so doctors measure IGF‑1 first. If IGF‑1 is high, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) follows; GH should drop below 1 ng/mL after a glucose load in normal individuals.

- Imaging: High‑resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the sellar region pinpoints tumor size, location, and invasiveness.

- Visual field assessment: Automated perimetry checks for optic chiasm compression.

- Additional hormone panels: To rule out co‑secretion of prolactin, ACTH, or TSH.

These steps not only confirm acromegaly but also guide treatment planning by showing how big the adenoma is and whether it’s pressing on nearby structures.

Treatment Options and What to Expect

Management aims to lower GH/IGF‑1 levels, shrink the tumor, and alleviate symptoms. The three main strategies are surgery, medication, and radiation.

| Treatment | Mechanism | Typical Use | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transsphenoidal surgery | Physical removal of the adenoma | First‑line for tumors < 1 cm, no major cavernous sinus invasion | CSF leak, nasal congestion, temporary hormone deficits |

| Somatostatin analogs (e.g., octreotide, lanreotide) | Bind somatostatin receptors, suppress GH release | Patients not cured by surgery or with macroadenomas | GI upset, gallstones, injection site pain |

| GH receptor antagonist (pegvisomant) | Blocks GH action at peripheral tissues | Used when somatostatin analogs fail to normalize IGF‑1 | Liver enzyme elevation, injection site reactions |

| Radiation therapy (SRS or conventional) | Gradual tumor shrinkage via DNA damage | Adjunct when surgery/meds insufficient | Delayed hypopituitarism, radionecrosis (rare) |

Transsphenoidal surgery, performed through the nose, offers the best chance of cure when the adenoma is small and well‑contained. Experienced neurosurgeons achieve remission rates of 70‑90 % in such cases. Larger or invasive tumors often need medication first to shrink the mass, making surgery safer.

Somatostatin analogs are injected monthly and can control GH in about 60‑70 % of patients. Pegvisomant, given daily, directly blocks GH receptors and normalizes IGF‑1 in up to 90 % of resistant cases, but it does not shrink the tumor, so imaging follow‑up remains essential.

Radiation therapies, especially stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), provide long‑term tumor control but may take several years to lower hormone levels. They’re usually reserved for patients who cannot undergo further surgery or who have persistent disease despite medication.

Living with Acromegaly After Treatment

Even after successful therapy, regular monitoring is crucial. IGF‑1 should be checked every 6-12 months, and MRI scans are recommended every 1-3 years to catch any regrowth early. Lifestyle tweaks-maintaining a healthy weight, regular cardiovascular exercise, and balanced nutrition-help mitigate the metabolic risks that often accompany acromegaly.

Support groups, both online and in‑person, can provide emotional relief. Many patients find that sharing experiences about facial changes, joint pain, or the psychological impact of a “different” appearance reduces isolation. In Canada, organizations like the Canadian Pituitary Foundation offer resources and connect patients with specialists across the country.

Family members also play a role. Simple adjustments-like buying shoes a size larger or modifying workstations for joint comfort-can make daily life smoother. Open communication with endocrinologists ensures that any new symptoms trigger timely investigations.

Key Takeaways

- A pituitary tumor that secretes excess growth hormone is the main cause of acromegaly.

- Symptoms appear gradually; early recognition hinges on noticing changes in hand, foot, and facial size.

- Diagnosis relies on IGF‑1 testing, oral glucose suppression test, and MRI imaging.

- Treatment combines surgery, medication, and sometimes radiation, tailored to tumor size and hormone levels.

- Lifelong monitoring and lifestyle management are essential for long‑term health.

Can acromegaly develop without a pituitary tumor?

Rarely, yes. A few cases stem from ectopic growth‑hormone‑releasing tumors outside the pituitary, such as in the lungs or pancreas. However, more than 95 % of acromegaly patients have a pituitary adenoma.

How soon after surgery can hormone levels normalize?

If the adenoma is completely removed, IGF‑1 can fall to normal within weeks to a few months. Residual tissue may keep levels elevated, requiring adjunct medication.

Is acromegaly hereditary?

Most cases are sporadic, but a small percentage stem from genetic syndromes like MEN 1 (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1) or familial isolated pituitary adenomas. Genetic counseling is advised for those with a family history.

What lifestyle changes help manage acromegaly?

Maintain a balanced diet low in refined carbs, stay active with cardio and strength training, and monitor blood pressure and glucose regularly. Weight control reduces cardiovascular strain, a major cause of mortality in acromegaly.

Can medication alone cure acromegaly?

Medications can normalize GH and IGF‑1 levels in most patients, but they rarely shrink the tumor enough to be considered a cure. Surgery remains the definitive option for cure when feasible.

Andrew Wilson

October 23, 2025 AT 21:28Yo guys, let me lay it straight – you can’t just brush off those weird changes in your hands or face and keep scrolling on TikTok, it's a BIG deal.

Acromegaly isn’t some mythic curse, it’s a real medical nightmare caused by that sneaky pituitary tumor hijacking your hormones.

If you ignore the signs, you’re basically signing away your own health and putting extra strain on the healthcare system.

Think about the people who end up with heart attacks or diabetes because they waited too long – that’s on us for not paying attention.

Everyone should know the classic symptoms: enlarged shoes, jutting jaw, thick skin – they’re not just “getting older”.

Doctors rely on IGF‑1 tests and MRI scans, but if the patient never shows up, the labs sit idle.

Early diagnosis can slash the risk of cardiovascular disease by a huge margin, so spreading awareness is a moral duty.

Don’t be that person who says “I didn’t know”, because the info is out there on Reddit, WebMD, and even the CDC.

Take a minute to get checked if you notice any of those tell‑tale signs – it could save your life.

And it’s not just about you, your family, friends, coworkers all benefit when you get treated early.

We should all push for better screening protocols in primary care, not wait until the tumor grows big enough to mess with vision.

That’s why I’m shouting from the rooftops: educate yourself, talk to your doc, and don’t let a silent tumor dictate your future.

Even if you feel fine, the hormone mess can be silently wrecking your metabolism.

Bottom line: take responsibility, get tested, and encourage others to do the same – it’s the decent thing to do.

Let's stop the complacency and make acromegaly a thing of the past.

Kristin Violette

October 23, 2025 AT 21:30Kristin here – thanks for spotlighting the urgency, Andrew. To flesh out the diagnostic pathway, clinicians often start with a fasting IGF‑1 assay because it reflects integrated GH secretion over 24 hours, followed by an oral glucose tolerance test to confirm lack of GH suppression. MRI with contrast is the gold standard for delineating micro‑ versus macro‑adenomas and assessing cavernous sinus invasion. From a therapeutic standpoint, the decision algorithm hinges on tumor size, hormonal control, and patient comorbidities, which is why a multidisciplinary pituitary board is invaluable. Early surgical remission rates approach 80 % for non‑invasive microadenomas, whereas somatostatin analogs provide biochemical control in roughly two‑thirds of medically managed cases. Incorporating these nuances into patient education can demystify the process and empower shared decision‑making.

Theo Asase

October 23, 2025 AT 21:31Look, you’re all dancing to the same pharma‑sponsored script, and you think surgery is the cure? Wake up! The drug companies have got a stranglehold on somatostatin analogs, feeding us endless injections while they line their pockets. They’ll never let a cheap, effective cure surface because that’d tank their profits. And don’t even get me started on the “multidisciplinary pituitary board” – a euphemism for bureaucratic red tape designed to keep patients in perpetual treatment cycles. The truth is, many of these tumors could be managed with simple lifestyle interventions if the establishment didn’t sabotage the data. It’s time we demand transparency and push back against the elite medical cartel.

Selina M

October 23, 2025 AT 21:33Hey folks, just wanted to say that staying active and keeping a healthy diet really helps with the metabolic side‑effects of acromegaly – even if you’re on meds.

tatiana anadrade paguay

October 23, 2025 AT 21:35Great summary! For anyone embarking on treatment, remember to schedule regular IGF‑1 checks and keep a diary of any new symptoms; this makes follow‑up appointments far more productive.

Nicholai Battistino

October 23, 2025 AT 21:36Check the pituitary MRI early.

Suraj 1120

October 23, 2025 AT 21:38Look, the checklist you suggest is fine, but most patients never get the full panel because insurance companies block the extra labs, forcing them to rely on guesswork. It’s a systemic issue that needs overhaul, not just a personal diary.

Shirley Slaughter

October 23, 2025 AT 21:40Shirley chiming in – the psychological impact of facial changes can be as burdensome as the physical symptoms. Cognitive‑behavioral strategies and support groups are essential components of a holistic treatment plan; don’t underestimate them.

Sean Thomas

October 23, 2025 AT 21:41Everyone loves their “support groups”, but they’re just sheep pens where the pharma reps drop flyers for the latest injections. Real freedom comes from pushing for surgical cures and exposing how the “holistic” narrative keeps us drug‑dependent.

Aimee White

October 23, 2025 AT 21:43Imagine a world where the pituitary tumor is not a monster but a signal that our bodies are rebelling against a toxic, industrial diet – the truth is hidden behind layers of corporate medical propaganda, waiting for us to decode it.