Spondylolisthesis: Understanding Back Pain, Instability, and Fusion Options

When your lower back aches after standing too long, and your hamstrings feel tighter than ever, it might not just be from sitting at a desk all day. For about 6% of adults, that discomfort comes from something more specific: spondylolisthesis. It’s not a muscle strain. It’s not just aging. It’s when one of the bones in your lower spine slips forward over the one below it-usually between L5 and S1. This isn’t rare. It’s common, especially in people over 50, and it’s often the hidden cause of chronic back pain that doesn’t respond to rest or painkillers.

What Exactly Is Spondylolisthesis?

Spondylolisthesis comes from two Greek words: spondylo for vertebra and olisthesis for slip. So, literally, a slipping vertebra. It’s not a fracture you can see on an X-ray unless you know what to look for. The slippage is measured as a percentage of how far the top vertebra has moved over the one beneath it. That’s called the Meyerding grade. Grade I is mild-less than 25% slip. Grade IV? That’s serious-75% to 100% slippage. Most cases fall into Grade I or II, but even those can cause real pain. There are five main types, and knowing which one you have changes everything. The most common in adults over 50 is degenerative spondylolisthesis. It happens because arthritis wears down the joints and discs in your spine. The bones lose their grip on each other and start to slide. This type accounts for about 65% of all adult cases. In younger people, especially athletes, it’s often isthmic-caused by a tiny stress fracture in the part of the bone that connects the joints. Gymnasts, weightlifters, and football players are at higher risk because their sport forces the spine into repeated backward bends.Why Does It Hurt? It’s Not Just the Slip

Here’s the thing: not everyone with a slipped vertebra feels pain. About half of people with spondylolisthesis never have symptoms. But when pain shows up, it’s usually deep in the lower back, radiating into the buttocks and thighs. It feels like a dull, constant ache that gets worse when you stand or walk and improves when you sit or lean forward. That’s because leaning forward opens up the space between the bones, taking pressure off the nerves. Tight hamstrings are a classic sign. Around 70% of people with this condition have them-not because they’re not stretching, but because the body is trying to protect the spine. The hamstrings pull tight to limit movement and reduce strain on the unstable joint. You might also notice stiffness, trouble walking long distances, or even a swayback posture. In advanced cases, the upper spine can start to curve backward, creating a roundback appearance. If the slip is severe-Grade III or IV-nerve compression becomes likely. About 35% of these patients feel tingling, numbness, or weakness in one or both legs. That’s called radiculopathy. In the worst cases, it leads to neurogenic claudication: leg pain that forces you to stop walking after just a few minutes, then eases when you sit down. Studies show people with high-grade slips are nearly three times more likely to develop this than those with mild slippage.How Is It Diagnosed?

Your doctor won’t guess. They’ll start with standing X-rays-because slippage changes when you’re upright. A lateral view shows exactly how far the bone has moved. But X-rays only show bone. To see if nerves are pinched, you’ll need an MRI. That’s the gold standard for checking disc herniation, spinal stenosis, or inflammation around the nerves. A CT scan might be used if the doctor suspects a fracture in the pars interarticularis, especially in younger patients. The key is matching symptoms to imaging. Someone with a Grade I slip and severe pain might have more disc degeneration than slippage. Research shows disc wear correlates strongly with age and how long symptoms have lasted-not with the degree of slip. That means treatment shouldn’t just focus on fixing the position of the bone. It should focus on what’s causing the pain: inflammation, nerve pressure, muscle imbalance.

Conservative Treatment: What Actually Works

Most people don’t need surgery. In fact, 80% of cases improve with non-surgical care. The first step? Stop what makes it worse. Avoid heavy lifting, backward bends, and high-impact sports. If you’re a runner or a weightlifter, you’ll need to modify your routine. Physical therapy is the cornerstone. Not just stretching. Not just core work. A targeted program that combines hamstring flexibility, core stabilization, and posture retraining. Studies show it takes 12 to 16 weeks of consistent therapy to see real results. And adherence? Only about 65% of people stick with it long enough. That’s why many give up too soon. Medications help manage pain but don’t fix the problem. NSAIDs like ibuprofen reduce inflammation. Epidural steroid injections can calm down nerve irritation for a few months-useful if you’re trying to get through physical therapy or delay surgery. But they’re not a long-term fix.Fusion Surgery: When It’s Time to Consider It

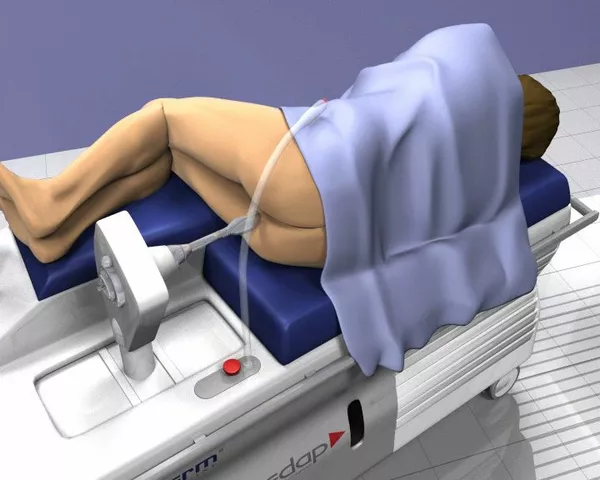

If you’ve tried 6 to 12 months of conservative care and your pain still limits walking, sleeping, or working, surgery becomes a real option. Spinal fusion is the most common procedure. The goal isn’t just to stop the slip-it’s to stop the pain by fusing the unstable bones together so they can’t move. There are three main ways to do it:- Posterolateral fusion (55% of cases): Bone graft is placed along the back of the spine, and screws and rods hold everything in place while the bone grows together.

- Interbody fusion (35%): The damaged disc is removed and replaced with a spacer filled with bone graft. This restores disc height and opens up the space where nerves exit the spine. Techniques include PLIF and TLIF.

- Minimally invasive fusion (10%): Smaller incisions, less muscle damage, faster recovery. Often used with interbody techniques.

What You Need to Know Before Surgery

Fusion isn’t a quick fix. It’s a major procedure with a long road to recovery. You’ll need 6 to 8 weeks of restricted activity. Physical therapy lasts 3 to 6 months. Full healing can take up to 18 months. Your chances of success drop if you smoke. Smokers have over three times the risk of failed fusion (pseudoarthrosis). If your BMI is over 30, complication rates jump by 47%. That’s why pre-op optimization isn’t optional-it’s essential. And then there’s the risk of adjacent segment disease. About 18-22% of patients develop new problems in the spinal levels above or below the fusion within five years. That’s because the fused segment stops moving, so the adjacent levels take on extra stress. That’s why surgeons are getting pickier about who gets fused. New studies have identified 11 clinical and imaging markers that predict surgical success with 83% accuracy. That means fewer people get unnecessary operations.What’s New? Alternatives to Fusion

Fusion isn’t the only option anymore. For mild to moderate cases, dynamic stabilization devices are being used more often. These are implants that limit harmful movement but still allow some motion-like a soft brace inside your spine. Early data shows 76% success at five years, compared to 88% for fusion. Not as good, but worth considering if you want to avoid fusion. New FDA-approved interbody devices, introduced in 2022, are showing better fusion rates-89% at six months versus 82% with older models. And biologics like bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and stem cell therapies are pushing fusion success to 94% in high-risk patients. These aren’t standard yet, but they’re becoming more common in complex cases.What Should You Do Next?

If you’ve had lower back pain for more than 3-4 weeks, especially with leg symptoms, see a spine specialist. Don’t wait until you can’t walk. Get imaging. Get a clear diagnosis. Don’t assume it’s just "old age." If you’re told you need surgery, ask: What grade is my slip? What type is it? What’s the success rate for the technique they’re recommending? Are there alternatives? Are you a good candidate for motion-preserving options? Spondylolisthesis isn’t a death sentence. It’s a mechanical problem with mechanical solutions. The right treatment depends on your age, your slip, your symptoms, and your goals-not just on what’s easiest for the doctor to do.Can spondylolisthesis heal without surgery?

Yes, in most cases. About 80% of people with spondylolisthesis improve with physical therapy, activity modification, and pain management. Surgery is only considered if symptoms persist for 6 to 12 months despite conservative care and significantly affect daily life.

Is walking bad for spondylolisthesis?

Walking can worsen pain if the slip is high-grade or if nerves are compressed. But complete rest isn’t the answer. Low-impact walking, especially in a slightly bent-forward posture (like using a shopping cart for support), can help maintain mobility without overloading the spine. Avoid long walks or uneven terrain until symptoms improve.

Does a slipped vertebra always mean I need a fusion?

No. Many people have slippage without pain, and even those with pain often improve without surgery. Fusion is reserved for cases where conservative treatments fail, symptoms are severe, and imaging confirms nerve compression or instability. Surgeons now use predictive models to avoid unnecessary operations.

How long does recovery take after spinal fusion?

Initial recovery takes 6 to 8 weeks, with restrictions on lifting and bending. Physical therapy typically lasts 3 to 6 months. Full bone fusion and return to normal activity can take 12 to 18 months. Success rates are highest when patients follow rehab protocols closely and avoid smoking.

Can spondylolisthesis get worse over time?

Yes, especially in degenerative cases. Without treatment, the slip can progress slowly over years. High-grade slips are more likely to worsen and cause nerve damage. Early diagnosis and management can slow or stop progression. Monitoring with periodic X-rays is recommended for moderate to severe cases.

Lydia H.

January 20, 2026 AT 00:56Been dealing with this for years. The hamstring tightness is real - I thought I just needed to stretch more, but turns out my body was bracing itself. Learned to walk with a slight forward lean and it changed everything. No more sudden stops mid-walk. Just slow, steady, like a turtle with a plan.

Phil Hillson

January 20, 2026 AT 09:30So you're telling me the whole fusion thing is just big pharma and spine surgeons making bank off people who coulda just stopped lifting dumbbells

Josh Kenna

January 21, 2026 AT 23:51lol i got diagnosed with grade ii last year and my pt said dont do squats but i did them anyway and now my back feels like a rusty hinge but also kinda better idk maybe its placebo but i keep doing them anyway

Lewis Yeaple

January 22, 2026 AT 14:40It is imperative to note that the Meyerding classification system, while widely utilized, lacks sensitivity in detecting early-stage instability in the lumbar spine. The reliance on radiographic slippage percentages as the primary diagnostic criterion neglects the biomechanical contributions of paraspinal muscle atrophy and ligamentous laxity, which are often the true drivers of symptomatic progression.

Jackson Doughart

January 24, 2026 AT 13:51I’ve seen people come in with Grade IV slips and walk out pain-free after 18 months of PT and mindfulness. Others get fused and still can’t sit through a movie. There’s no one-size-fits-all. The body’s smarter than the scan.

Malikah Rajap

January 24, 2026 AT 17:39Wait - so you're saying the spine isn't just a stack of bones, but a living, breathing, *reactive* system? Like... it remembers trauma? And adapts? And that’s why stretching alone doesn’t fix it? I’ve been doing yoga for 12 years and now I’m crying. This makes so much sense. I’m going to tell my therapist.

Tracy Howard

January 25, 2026 AT 14:49Of course Americans think fusion is the answer. In Canada, we just tell people to stop being lazy and stand up straight. No surgery needed. Just discipline. And cold showers. And respect for your spine. You people are too soft.

Jake Rudin

January 27, 2026 AT 10:04But what if… the slip isn’t the problem? What if the pain is just the body’s way of saying: ‘You’ve been ignoring your breath, your posture, your grief, your unprocessed anger?’ The spine doesn’t slip - it whispers. And we’ve been yelling at it with NSAIDs and MRI machines instead of listening.

sujit paul

January 28, 2026 AT 16:50Let me tell you something the medical industry doesn’t want you to know. The entire concept of spondylolisthesis was invented by pharmaceutical conglomerates to sell spinal implants. The real cause? EMF radiation from 5G towers destabilizing the vertebral collagen matrix. I’ve seen it with my own eyes - in Kerala, where they use turmeric paste and chanting, no one has this condition. The West is poisoning you with titanium.

Astha Jain

January 30, 2026 AT 13:46so i had this thing and my doc said fusion but i just started doing tai chi and now i dont even feel it anymore like maybe its all in your head idk

Erwin Kodiat

January 31, 2026 AT 21:55My dad had this. Didn’t do surgery. Walked 2 miles every morning with a cane, drank green tea, and started meditating. Now he’s 82 and says his back is his best friend. Not because it’s perfect - because he stopped fighting it.

Valerie DeLoach

February 1, 2026 AT 17:54For anyone reading this and feeling overwhelmed: You’re not broken. Your body is adapting to years of movement patterns, stress, and maybe even emotional tension. Healing isn’t about fixing a bone - it’s about rebuilding trust with yourself. Slow down. Breathe. Find a therapist who understands somatic pain. You’re not alone.

Christi Steinbeck

February 3, 2026 AT 15:46STOP WAITING. If your pain is keeping you from your life - go see a specialist. Don’t wait for it to get worse. Don’t wait for insurance to approve. Don’t wait for someone to tell you it’s ‘just aging.’ You deserve to move without fear. Start today. Even if it’s just one stretch. You’ve got this.

Jacob Hill

February 4, 2026 AT 13:28Just wanted to add - if you’re considering fusion, ask about the use of BMP. It’s not magic, but it helped my cousin’s fusion heal 4 months faster than expected. Also, please, for the love of all that’s holy, quit smoking. I know it’s hard. But your spine will thank you in 18 months.