WHO Model Formulary: How International Standards Shape Access to Essential Generics

The WHO Model Formulary isn’t a list you’ll find on a hospital shelf or in a pharmacy’s computer system. It’s something bigger - a global blueprint that tells countries what medicines their people actually need to survive. And at its heart? Generics. Affordable, proven, life-saving generics.

Since 1977, the World Health Organization has been updating its Model List of Essential Medicines every two years. The 2023 version, the 23rd edition, includes 591 medicines. Nearly half of them - 273 to be exact - are generic versions of brand-name drugs. This isn’t an accident. It’s the deliberate strategy of a global health body that knows cost can be the difference between life and death.

What Makes a Medicine "Essential"?

Not every drug makes the cut. The WHO doesn’t pick medicines because they’re popular or profitable. They’re chosen based on hard data: proven effectiveness, safety, and cost-effectiveness. To qualify, a medicine must treat a condition that affects at least 100 people per 100,000. It needs to be backed by clinical trials - not just any trial, but high-quality ones. And it must be cheaper than alternatives, offering the most health benefit per dollar spent.

For example, a generic antibiotic like amoxicillin is included because it treats common infections like pneumonia and ear infections in kids. A generic antiretroviral like tenofovir is included because it keeps HIV from killing millions. These aren’t "nice to have" drugs. They’re the ones that keep health systems running when budgets are tight.

The list is split into two parts. The core list has the minimum medicines every basic health clinic should have - things like insulin, blood pressure pills, and painkillers. The complementary list includes drugs that need more expertise or monitoring, like cancer treatments or epilepsy medications. Both lists prioritize generics when they meet the same safety and effectiveness standards as the brand-name version.

How Generics Are Vetted - And Why It Matters

Just because a drug is generic doesn’t mean it’s safe. That’s why the WHO requires every medicine on the list to meet strict quality standards. Most generics must pass WHO Prequalification - a process that tests whether the drug works the same way as the original. This isn’t a rubber stamp. Manufacturers must prove their product has the same active ingredient, dissolves the same way in the body, and delivers the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream.

For drugs with a narrow therapeutic window - where even a small difference can cause harm - the bar is even higher. The acceptable range for bioequivalence is tighter: 90% to 111% compared to the original. That’s stricter than many national regulators require. This is why a generic HIV pill from a WHO-prequalified factory in India is trusted in Malawi, while a fake version from an unregulated source might kill someone.

By 2023, 92% of the generics on the WHO list had passed this prequalification. That number has grown from just 45% in 2010. It’s proof that global standards can push manufacturers to do better.

Why Countries Follow the List - And Why Some Don’t

More than 150 countries have created their own national essential medicines lists based on the WHO model. In Ghana, adopting these standards cut out-of-pocket medicine costs by nearly 30% between 2018 and 2022. In India, hospitals saved 35% on antibiotics by switching to WHO-recommended generics.

But adoption isn’t uniform. In Nigeria, despite having a national list based on the WHO model, only 41% of essential medicines were reliably available in health facilities in 2022. Why? Not because the list was wrong - because the supply chain broke down. Stockouts lasted an average of 58 days per medicine. In some places, the problem isn’t the medicine - it’s the trucks, the storage, the trained staff to give it out.

Even in wealthy countries, the WHO list matters - just differently. U.S. hospitals rarely use it for their internal formularies. But when they run global health programs - say, a clinic in Kenya or a refugee camp in Jordan - they turn to the WHO list. It’s the only standard everyone agrees on.

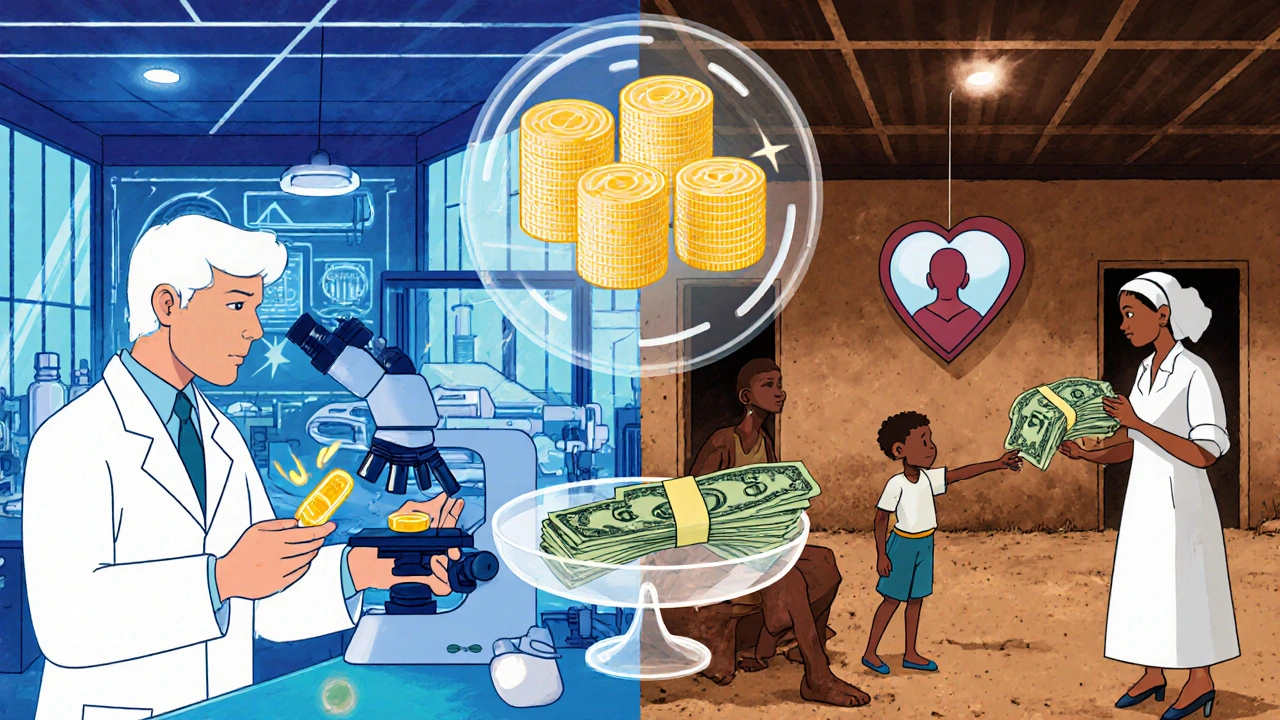

The Real Impact: Lower Prices, More Lives

The clearest proof of the WHO Model Formulary’s power? The price drop.

In 2008, a year’s supply of generic HIV drugs cost $1,076 per patient. By 2023, it was $119. That’s an 89% drop. Why? Because the WHO list created a global market for generics. When the Global Fund, UNICEF, and other agencies buy medicines, they only buy from prequalified manufacturers. That forced companies to compete on price and quality - not marketing.

Today, 85% of all medicines bought by global health programs follow the WHO list. That means billions of dollars are spent on generics that work - not on overpriced brands or fake drugs.

And it’s working. In 2003, only 800,000 people with HIV were on treatment. By 2022, that number was 29.8 million. That’s not just a statistic. That’s millions of parents alive to see their kids grow up.

Where the System Falls Short

But it’s not perfect.

Only 12% of new drugs approved between 2018 and 2022 made it onto the 2023 list. That’s because the WHO waits for long-term data. A new cancer drug might be brilliant, but if there’s no proof it lasts five years or is affordable, it won’t be included. Critics say this delays access. Supporters say it prevents wasting money on hype.

Another issue: most generic production is concentrated in just three countries - India, China, and the U.S. When supply chains break - like during the pandemic - shortages hit hardest in low-income countries. In 2021, 62% of them reported critical shortages of essential antibiotics.

And then there’s the problem of fake medicines. WHO surveillance found that 10.5% of essential medicine samples in low- and middle-income countries were substandard or falsified. Antibiotics and antimalarials were the most common targets. Even with prequalification, the system can’t control every pill sold on a street corner.

What’s Changing Now

The WHO is adapting. The 2023 list included seven biosimilars - cheaper versions of complex biologic drugs used for cancer and autoimmune diseases. It also added more pediatric formulations. In 2019, only 29% of medicines had child-friendly doses. Now it’s 42%. That’s huge. A child shouldn’t have to swallow a crushed adult pill.

In September 2023, the WHO launched a free app that lets pharmacists and doctors in rural clinics check which medicines are on the list, how to use them, and where to buy prequalified versions. It’s been downloaded over 127,000 times in 158 countries.

And the focus is shifting. The Expert Committee now spends 20% of its time on implementation - how to get these medicines to people who need them - instead of just debating which drugs to include. That’s a big change.

What This Means for You

If you live in a wealthy country, you might never think about the WHO Model Formulary. But it’s why your generic blood pressure pill costs $4 instead of $400. It’s why a child in rural Bangladesh can get antibiotics for pneumonia. It’s why global health programs can treat HIV without going bankrupt.

It’s not glamorous. It doesn’t make headlines. But every time a generic drug is prescribed, dispensed, and taken - because it’s safe, affordable, and available - the WHO Model Formulary did its job.

The real test isn’t how many medicines are on the list. It’s how many people actually get them. And that’s where the work continues.

Sheldon Bazinga

November 21, 2025 AT 18:36Sandi Moon

November 23, 2025 AT 05:01And let us not forget: the very notion of ‘essential’ medicines is a colonial relic, imposed by Western technocrats who’ve never seen a rural clinic. The real tragedy? We’ve been conditioned to believe this is liberation.

Kartik Singhal

November 24, 2025 AT 01:55Meanwhile, US pharma patents keep prices sky-high while we supply the world. But hey, at least we get to play nice with the UN and get our name on the list. 🇮🇳💊 #GlobalSupplyChainReality

Logan Romine

November 25, 2025 AT 00:26It’s like giving a starving man a map to a buffet… and then charging him $400 for the fork.

Genius. 🤖💀

Pravin Manani

November 25, 2025 AT 06:46What’s often overlooked is the epistemic shift: from physician-centric formularies to evidence-based, population-level pharmacoeconomic prioritization. This isn’t just about drugs - it’s about redefining health as a public good, not a market commodity.

Leo Tamisch

November 25, 2025 AT 09:08It’s not altruism. It’s capitalism with a conscience filter. 😏

Daisy L

November 26, 2025 AT 07:29Anne Nylander

November 26, 2025 AT 12:01Franck Emma

November 28, 2025 AT 07:17Eliza Oakes

November 29, 2025 AT 04:59Clifford Temple

November 29, 2025 AT 22:53Steve Harris

November 30, 2025 AT 04:38Yes, supply chains break. Yes, fake drugs exist. But the solution isn’t to throw out the system - it’s to fund the trucks, train the pharmacists, and build local capacity. The WHO’s new focus on implementation? That’s the real breakthrough.

And that app? I downloaded it. I use it every day. It’s saved lives in villages where Google doesn’t work. That’s not bureaucracy - that’s grace.