Understanding Controlled Substance Labels and Schedule Codes: What You Need to Know

When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, the label on the bottle isn’t just a reminder to take your medicine. For controlled substances, that label carries legal weight. It tells you what drug you’re taking, how much, and when you can get more - but it also reveals something deeper: the federal government’s classification of that drug’s risk. These classifications are called schedule codes, and they’re not arbitrary. They’re based on science, abuse potential, and medical use - and they directly affect how your doctor writes the prescription, how the pharmacist fills it, and even whether you can refill it at all.

What Are Schedule Codes and Why Do They Matter?

The U.S. government uses five schedules - I through V - to classify controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970. This system was created to balance access to necessary medications with the need to prevent abuse and diversion. Each schedule has strict rules around prescribing, dispensing, and recordkeeping. The DEA assigns every controlled substance a unique code number, often labeled on pharmacy labels as "CSA SCH" followed by the schedule number.Here’s the core idea: the higher the schedule number, the lower the risk. Schedule I drugs have no accepted medical use and the highest abuse potential. Schedule V drugs have the lowest risk and are often available with minimal restrictions. But the system isn’t perfect. Some drugs, like codeine, appear in multiple schedules depending on their formulation - pure codeine is Schedule II, while a cough syrup with 15 mg per 5 mL is Schedule V. That’s why you can’t assume a drug’s schedule just by its name.

How the Five Schedules Work in Practice

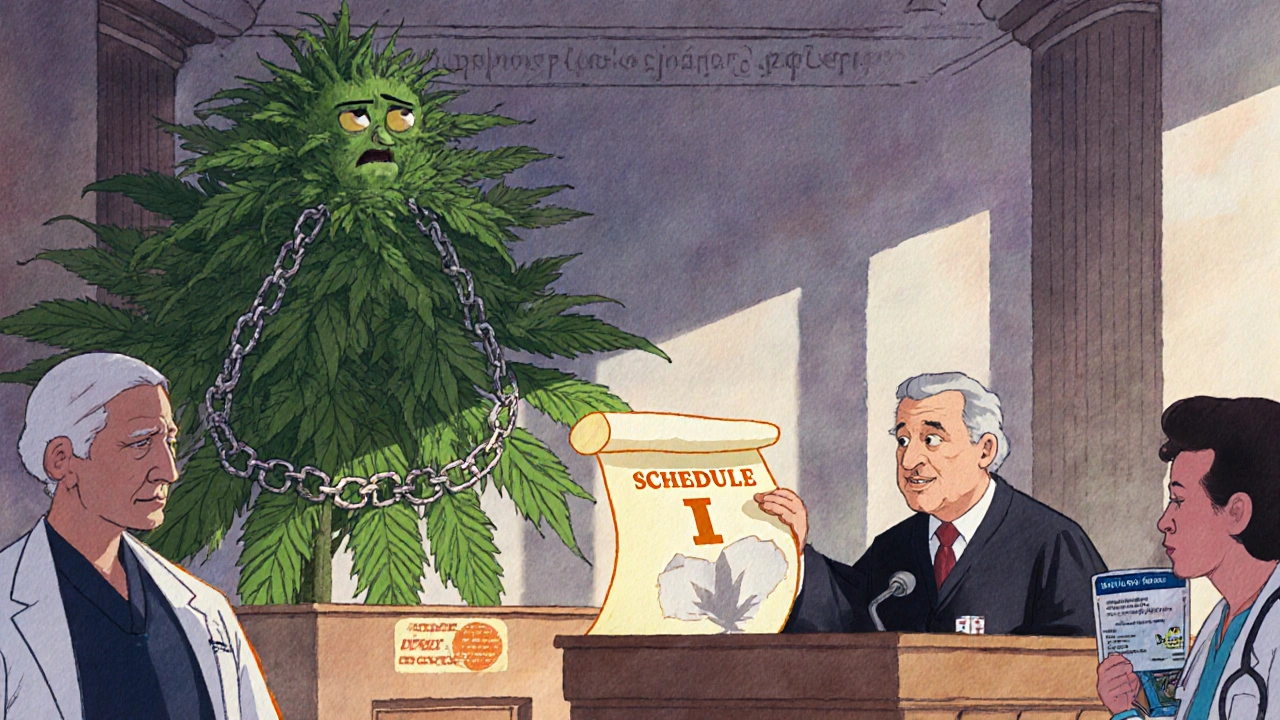

Schedule I - These drugs are illegal for medical use in the U.S. Examples include heroin, LSD, and (as of 2025) marijuana under federal law. Even if your state allows medical marijuana, it remains Schedule I federally. That means no prescriptions, no DEA registration, and no pharmacy can legally dispense it under federal authority. This creates real conflicts for patients and providers in states where cannabis is legal.

Schedule II - These are powerful drugs with high abuse potential but accepted medical uses. Think oxycodone, fentanyl, Adderall, and morphine. Prescriptions for these cannot be refilled. Each one is a one-time use - if you run out, you need a new prescription from your doctor. Most states require these to be written on tamper-resistant paper, though electronic prescriptions are allowed in some cases. Pharmacists spend extra time verifying these prescriptions - one nurse reported it takes 15 minutes longer to process a Schedule II than a regular prescription.

Schedule III - These have moderate to low abuse potential. Common examples include hydrocodone combined with acetaminophen (like Vicodin), ketamine, and anabolic steroids. You can refill these up to five times within six months. Electronic prescriptions are standard. In fact, hydrocodone combinations are the most frequently dispensed controlled substances in U.S. pharmacies, making up a large chunk of the 92.7% of controlled scripts that fall in Schedules III-V.

Schedule IV - Lower abuse risk still. Benzodiazepines like Xanax and Valium, sleep aids like Ambien, and tramadol fall here. Refills are allowed up to five times in six months, and electronic prescriptions are fully permitted. Many patients don’t realize these are controlled substances because they’re so commonly prescribed. But they still carry risks - especially when mixed with alcohol or opioids.

Schedule V - The lowest risk category. These include cough syrups with small amounts of codeine (under 200 mg per 100 mL), antidiarrheal meds with diphenoxylate, and pregabalin. Some can be sold over-the-counter in limited quantities with pharmacist oversight. In many states, you don’t even need a prescription for a small bottle of codeine cough syrup - but you still have to ask the pharmacist, and they can refuse if they think it’s being misused.

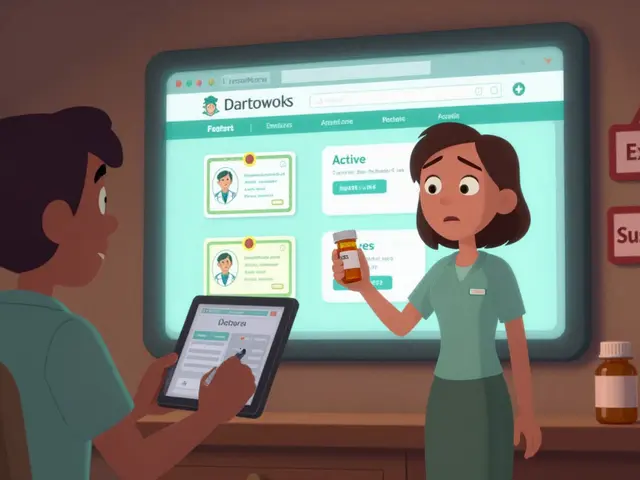

What You’ll See on a Controlled Substance Label

The label on your prescription bottle isn’t just instructions. It’s a legal document. For controlled substances, it must include:

- The patient’s full name and address

- The prescriber’s name, address, and DEA registration number

- The drug name and strength

- The quantity dispensed

- Directions for use

- The date the prescription was issued

- The pharmacy’s name and address

- The CSA Schedule code - usually printed as "CSA SCH II" or "CSA SCH IV"

Some pharmacies also include a warning like "Controlled Substance - No Refills" for Schedule II drugs. If you see that, don’t assume it’s a mistake. It’s the law. You can’t get a refill unless your doctor writes a new prescription.

Why the System Is Both Helpful and Flawed

The scheduling system gives structure. Addiction counselors use it to help patients understand relative risks - a Schedule II opioid is far more dangerous than a Schedule IV sleep aid. Pharmacists rely on it to know how to handle each script. And regulators use it to track where drugs go.

But the system has glaring gaps. Cannabis remains Schedule I despite being legally prescribed by doctors in 38 states and used by over 2 million patients. The DEA’s own scientific review in 2023 recommended moving it to Schedule III - a change that could come as early as 2026. Meanwhile, synthetic drugs like fentanyl analogs are being added to Schedule I faster than ever, with 17 new substances emergency-scheduled between 2022 and 2023.

Experts agree: the system needs updating. A 2022 Rand Corporation survey found 82% of professionals believe we’ll need a six- or seven-schedule system within 15 years to better reflect real-world risk. Right now, the system lumps together drugs with vastly different profiles - for example, a low-dose stimulant for ADHD and a high-dose opioid for cancer pain are both Schedule II, even though their risks and uses are worlds apart.

What This Means for You as a Patient

If you’re taking a controlled substance, here’s what you need to know:

- Check the schedule code on your label. If it says "CSA SCH II," you won’t get refills - plan ahead.

- Don’t assume a drug is safe just because it’s not Schedule I. Schedule IV drugs like Xanax can be addictive, especially if taken long-term.

- Keep your prescriptions secure. Schedule II and III drugs are targets for theft and diversion.

- Ask your pharmacist if you’re unsure about refill rules. They’re trained to explain them.

- If you’re prescribed a Schedule II drug, make sure your doctor’s DEA number is on the prescription. If it’s missing, the pharmacy can’t fill it.

And if you’re switching doctors or pharmacies, bring your current prescription bottles with you. That way, the new provider can see exactly what you’ve been taking and what schedule it’s under. This avoids delays and confusion.

What’s Changing in the Near Future

The most anticipated change is the possible rescheduling of cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule III. If that happens, doctors could prescribe it like any other controlled medication, pharmacies could stock it, and insurance might cover it. That shift alone would reshape how millions of patients manage chronic pain, epilepsy, and PTSD.

Other changes are coming too. The DEA is working to cut the average time to schedule a new drug from 24 months to 12 months by 2025. That means faster responses to new synthetic opioids and designer drugs. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry spends over $2 billion a year just to comply with these rules - a cost that eventually affects your prescription price.

For now, the system is what it is: a mix of science, politics, and outdated assumptions. But understanding it helps you navigate your care more confidently. You’re not just taking a pill - you’re interacting with a federal regulatory framework that’s been in place for over 50 years. Knowing the schedule code on your label isn’t just useful - it’s essential for safe, legal, and effective treatment.

What does CSA SCH III mean on my prescription label?

CSA SCH III stands for Controlled Substances Act Schedule III. It means your medication has a moderate to low potential for abuse and dependence. You can refill this prescription up to five times within six months, and it can be prescribed electronically. Common examples include hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Vicodin), ketamine, and anabolic steroids.

Can I refill a Schedule II prescription like oxycodone?

No, Schedule II prescriptions cannot be refilled under federal law. Each prescription is valid for one fill only. If you need more medication, your doctor must write a new prescription. This rule exists because Schedule II drugs have a high potential for abuse and physical dependence. Even if you have leftover pills, you cannot legally use them beyond the original prescription’s scope.

Why is marijuana still Schedule I if it’s legal in my state?

Marijuana remains federally classified as Schedule I because the U.S. government has not yet changed its classification under the Controlled Substances Act, despite medical legalization in 38 states. Schedule I means it’s considered to have no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse under federal law. However, the Department of Health and Human Services recommended rescheduling it to Schedule III in August 2023, and a final decision is expected soon. Until then, state and federal laws conflict, creating legal gray areas for patients and providers.

Can I get Schedule V drugs without a prescription?

In some states, yes - but only under strict limits. Schedule V medications, like certain cough syrups with small amounts of codeine (under 200 mg per 100 mL), may be sold over-the-counter with pharmacist supervision. You’ll need to ask the pharmacist, show ID, and the amount you can buy is limited. Pharmacists can refuse sales if they suspect misuse. These drugs have very low abuse potential, so restrictions are minimal compared to higher schedules.

How do I know if my doctor is authorized to prescribe controlled substances?

Your doctor must have a DEA registration number, which appears on every controlled substance prescription. It starts with two letters (like "AB" or "MC") followed by seven digits. If the prescription doesn’t include this number, the pharmacy cannot legally fill it. Doctors must apply for this number through the DEA, and it takes 4-6 weeks to process. If you’re unsure, ask your doctor’s office for their DEA number - it’s a legal requirement to provide it.

deepak kumar

November 18, 2025 AT 11:21Just got my Vicodin refill and saw CSA SCH III on the label-never realized how much legal weight that tiny code carries. In India, we don’t have this level of labeling, so seeing it here felt like a whole new world. Thanks for breaking it down so clearly.

Jeff Hakojarvi

November 19, 2025 AT 05:18Biggest thing people miss? Schedule II isn’t just about addiction-it’s about how the system treats you like a suspect. I had to call my doctor three times just to get a new script for oxycodone after a surgery. They didn’t trust me. The system doesn’t care if you’re in pain, only if you’re ‘abusing’.

kim pu

November 19, 2025 AT 20:29CSA SCH IV? More like CSA SCH ‘I’m just here to get high but not get caught.’ Xanax is basically the gateway drug for middle-class burnout. And don’t even get me started on how pharmacies treat you like a criminal if you ask for a refill. It’s not medicine-it’s corporate-controlled anxiety vending machines.

malik recoba

November 19, 2025 AT 22:08i never knew the dea number had to be on the label. i thought it was just for the doc. my last script got bounced because of it. pharmacist was nice but i felt so dumb. now i always check before i leave. thanks for the heads up.

Sarbjit Singh

November 21, 2025 AT 17:56Sameer here from India 🇮🇳. We don't have schedules like this, but I've seen friends struggle with opioid access. This system is rigid but maybe necessary? Still, if someone needs pain relief, why make it so hard? 🤔

Angela J

November 23, 2025 AT 09:37They say marijuana is Schedule I because it’s dangerous… but what if it’s because they’re scared of people waking up? What if the DEA’s afraid of a world where you don’t need Big Pharma to feel okay? They’re hiding something. And now they want to move it to Schedule III? Too little, too late. They’ve been lying for 50 years.

Sameer Tawde

November 25, 2025 AT 08:56Check your label. Know your schedule. Plan ahead. Simple. No drama. No guesswork. If it’s SCH II, don’t wait till the last pill. Call your doc early. Life’s easier that way. 🚀

Timothy Uchechukwu

November 25, 2025 AT 21:03Why are we even talking about this like its some sacred system? America locks people up for weed while letting pharma pump out opioids like candy. This isn't science its capitalism with a badge. You think a DEA number makes it legit? Nah. It just means they got the right paperwork to profit from your pain

Ancel Fortuin

November 26, 2025 AT 10:53They say Schedule V cough syrup is low risk… but I’ve seen kids in the hood trade it like candy. You think the DEA cares? Nah. They only care when it’s ‘abused by the wrong people.’ This whole system is rigged to control the poor while letting rich folks get Adderall for focus and Xanax for sleep without blinking.

Hannah Blower

November 28, 2025 AT 07:37Let’s be real-the scheduling system is a relic of 1970s moral panic dressed up in pharmacological jargon. Schedule I isn’t about science, it’s about cultural fear. Cannabis was demonized because it empowered marginalized communities to self-medicate and relax. The DEA didn’t classify drugs-they classified people. And now we’re stuck with a bureaucratic monument to racism and prohibitionism. We need a new taxonomy, not a rebrand.

Gregory Gonzalez

November 29, 2025 AT 22:03How quaint. You think the average patient actually reads the CSA SCH label? Or do they just swallow the pill and assume the system knows best? The real tragedy isn’t the scheduling-it’s that we’ve outsourced our medical autonomy to a bureaucracy that doesn’t care if you live or die, as long as the forms are filled correctly.

Ronald Stenger

November 30, 2025 AT 04:45Let’s not pretend this is about safety. This is about control. The DEA schedules drugs based on lobbying power, not data. Look at fentanyl analogs-emergency scheduled in months. But kratom? Still Schedule I after 20 years of patient testimony. This isn’t science. It’s politics in a lab coat.

Samkelo Bodwana

December 1, 2025 AT 21:29I get that the system is flawed, but I also think it’s better than nothing. Back in South Africa, we had zero oversight on pain meds-people were hoarding tramadol like it was candy. Here, at least there’s a paper trail. Yeah, it’s bureaucratic, yeah, it’s slow, but it keeps drugs out of the wrong hands. Maybe we need more nuance, but don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. The structure saves lives, even if it’s clunky.

Emily Entwistle

December 3, 2025 AT 02:45Just got my Ambien script and saw CSA SCH IV… 😌 honestly, I’m just glad I can still get it. My anxiety’s been wild lately. But wow, I never realized how much of a control system this is. I thought I was just getting sleep… turns out I’m participating in federal regulation. 🤯

Dave Pritchard

December 4, 2025 AT 00:07One thing I’ve learned as a nurse: the schedule code tells you more about the law than the drug. A Schedule II opioid and a Schedule II stimulant are worlds apart in how they affect the body-but the rules treat them the same. We need to fix that. Not just update the system-rebuild it around actual medical need, not legal convenience.