TB Health Disparities: Why Some Groups Suffer More

Ever wonder why TB still kills thousands in some neighborhoods while other places see only a few cases? The answer isn’t just biology – it’s a mix of poverty, crowded housing, limited health services, and other social factors that push the disease into the most vulnerable.

When you hear "TB" most people think of a cough and night sweats, but the real story starts long before the symptoms appear. People living in low‑income areas often lack proper nutrition, have jobs that keep them in close quarters, and face barriers to getting tested or treated. Those conditions give the bacteria a perfect foothold.

What Drives TB Disparities?

First, economic status matters. Families without steady income can’t afford regular doctor visits, and many public clinics are under‑funded. This means delayed diagnosis and longer periods of infectiousness.

Second, housing density is a silent booster. Overcrowded apartments or shelters make it easy for airborne bacteria to jump from person to person. Even a short stay in a cramped space can raise infection risk.

Third, co‑infections like HIV amplify the problem. HIV weakens the immune system, so people with HIV are far more likely to develop active TB. In regions where HIV rates are high, TB numbers soar.Fourth, stigma stops people from seeking help. If a community views TB as a sign of personal failure, members hide symptoms and avoid treatment, feeding the cycle of transmission.

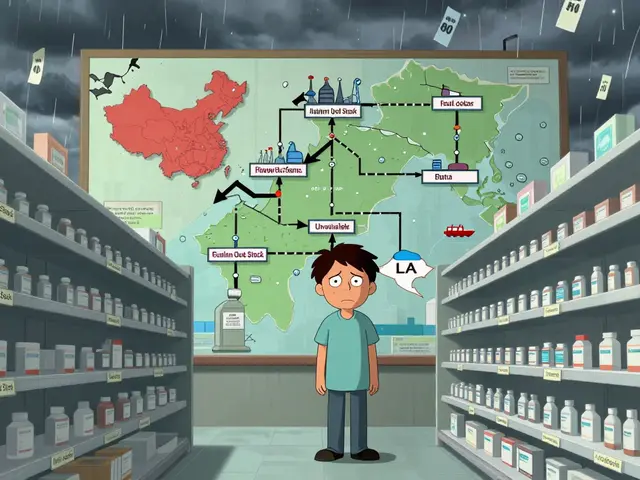

Finally, access to quality medication is uneven. Some countries have robust drug‑delivery programs, while others struggle with shortages or counterfeit pills. When treatment isn’t reliable, drug‑resistant TB emerges, making the disease even harder to control.

How to Reduce the Gap

Addressing TB health disparities means tackling these root causes, not just the bacteria. Improving income support and housing conditions can cut transmission before it starts. Simple steps like ventilation upgrades in dorms or shelters have already lowered case numbers in several cities.

Expanding free testing sites and mobile clinics brings care to where people live, cutting the time between infection and diagnosis. Pairing TB screening with HIV services boosts early detection for both illnesses.

Education campaigns that normalize talking about TB reduce stigma. When community leaders share stories of successful treatment, neighbors feel safer seeking help.

On the policy side, governments need to guarantee a steady supply of quality medicines and fund short‑course treatment programs that finish in six months instead of years. International donors can help by supporting drug‑resistance labs and training local health workers.

At the individual level, anyone can play a part: keep windows open when possible, wear masks if you’re coughing, and encourage friends to get tested if they’ve been exposed.

Closing the TB gap isn’t a quick fix, but with coordinated effort—better housing, stronger health systems, and less stigma—we can move toward a world where TB doesn’t pick its victims based on zip code or income.

How Tuberculosis Affects Indigenous Communities - Risks, History, and Solutions

Explore the historic and present impact of tuberculosis on Indigenous communities, key factors driving disparities, and effective strategies for prevention and care.

Categories

- Medications (71)

- Health and Medicine (62)

- Health and Wellness (38)

- Online Pharmacy Guides (16)

- Nutrition and Supplements (9)

- Parenting and Family (3)

- Environment and Conservation (2)

- healthcare (2)

- prescription savings (1)